What Domain-Driven Design Looks Like in TypeScript

This post is primarily going to focus on implementing Domain-Driven Design (DDD) at a low-level in TypeScript in the UI, so if you're more interested in understanding what DDD is used for, read this post first.

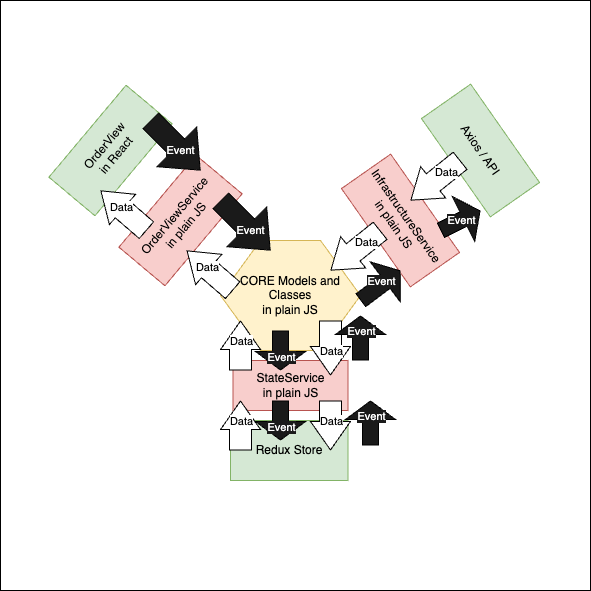

In this post, we will implement a full-blown hexagonal DDD architecture using the Singleton and Factory patterns along with a Facade pattern from Gang of Four. We will also avoid creating a nightmare of a dependency injection module resolution framework like we usually get in Angular or Nest. We want to keep it simple.

What we will build will end up looking like this architecturally, but with TypeScript and some naming changes:

Let's imagine a shopping website. We'll call it Shoppd. There are several pieces to this site:

- A landing page where the user can search for items that they want to buy.

- A search page where the user can see the results of their search.

- A shopping cart where the user can see any items that they have selected to buy, along with a price calculation for subtotals and the final total including taxes and shipping.

Shoppd has gone through many transformations over the years and has become a multinational megasite that handles lots of traffic every day. We'll assume that Shoppd is not a startup because, once again, if you are building a startup you don't need DDD - you need a slingshot or even a paper form for customers to fill out. These transformations for Shoppd have become more and more painful as the UI layer has turned over repeatedly every 3-5 years, first from jQuery, then to AngularJS, then to React, and then to Vue 2. You have also had to migrate from primarily storing state on the server side to $rootScope with a vanilla JavaScript object store to Redux to VueX. You have been tasked with creating a plan to future-proof the application so that future changes are much less painful as UI libraries become obsolete.

We're also going to do this with a little help from AI. AI changes how you plan to handle change over time organizationally, but it is not going to solve all of your problems and it still does not change the fundamentals we'll talk about here. Still, as we will see, some of the vocabulary we'll go over here could be very useful when you're creating a prompt for an AI agent to generate or refactor code. We'll take a deeper look at AI in a later post, but AI will be used a bit in this one in order to generate some of our code.

Let's focus on the initial user journey: a landing page where the user can search for items they want to buy. We're going to go on an implementation journey through the domain.

The AI Prompt

I spun up Cursor for this, and ran the following prompt through Claude 3.7 Sonnet.

It is not a simple prompt. However, Claude built a functioning site from this prompt, and almost followed my instructions exactly. This saved me hours of coding (which would have been happening over the course of a few nights and a weekend for this post since I'm writing this on my own time), and it's worth showcasing what Claude was capable of.

Prompt:

Create a React app with TypeScript using Domain-Driven Design principles and make the following files, along with Vitest unit tests for each file:

- LandingPageComponent: A React component to display a list of products fetched from 'https://fakestoreapi.com/products' (which returns an application/json payload). The LandingPageComponent should not call the API directly, but should invoke a

getProducts()method on the LandingPageFacade to initiate a fetch of the data, and should have aproductsstate variable that pulls in the fetched products from the LandingPageFacade, through the CoreDomain class, through the StateFacade class, from the store. This property should be reactive and should update anytime thatproductsis updated in the store. The only other class that the LandingPageComponent should directly interact with is the LandingPageFacade. It should be created in asrc/uidirectory. - LandingPageFacade: A TypeScript class that is implemented with a singleton class constructor in order to only instantiate one instance of the LandingPageFacade when it is invoked with

new LandingPageFacade(). The LandingPageFacade should serve as a pass-through facade between the LandingPageComponent and the CoreDomain class. The LandingPageFacade should use its getProducts method to invoke agetProducts()method on the CoreDomain class, and it should also have aproductsproperty that pulls in products from the CoreDomain through the StateFacade and the store. It should also be created in asrc/uidirectory. The Landing - CoreDomain: A TypeScript class that is implemented with a singleton class constructor so that only one instance is ever created when it is invoked with

new CoreDomain(). It should have a publicgetProductsmethod that invokes agetProductsmethod on the InfraFacade class. It should have a privatesetProductsmethod that invokes asetProductsmethod on the StateFacade when the getProducts call succeeds to set products in the store. If the call failsgetProductsshould set products to an empty array and invoke asetErrorsmethod on the StateFacade that sets theerrorsproperty in the store. It should also have aproductsvariable or getter that pulls in products in the store through the StateFacade. It should be created in asrc/domaindirectory. The CoreDomain class should only directly interact with the StateFacade and InfraFacade, and it should initialize this.stateFacade and this.infraFacade private variables on the class when the CoreDomain class is constructed. - InfraFacade: A TypeScript class that is implemented with a singleton class constructor so that only one instance is ever created when it is invoked with

new InfraFacade(). It should use thefetchAPI to make the call to 'https://fakestoreapi.com/products' when itsgetProductsis invoked and return the JSON response. The type of the response will look like:

{id: number;

title: string;

price: number;

description: string;

category: string;

image: string; // a URL}. The InfraFacade should be created in asrc/infradirectory. - StateFacade: a singleton TypeScript class that uses a singleton class constructor to only create one instance of StateFacade even if

new StateFacade()is invoked multiple times. It should expose a publicsetProductsmethod that sets the fetched products in a reactive array in a Redux store. It should also expose a publicproductsvariable that exposes the reactiveproductsarray from the Redux store as a pass-through reference. The StateFacade should be created in asrc/statedirectory. - ShoppdStore: a Redux store that sets and gets an array of

products, and returns an empty array if no products are set in the store. The ShoppdStore should be created in asrc/statedirectory. - Finally, initialize the CoreDomain (and the ShoppdStore if necessary) by invoking

new CoreDomain()in src/App.tsx during app bootstrap. All other classes should be initialized in the constructors of their consuming classes.

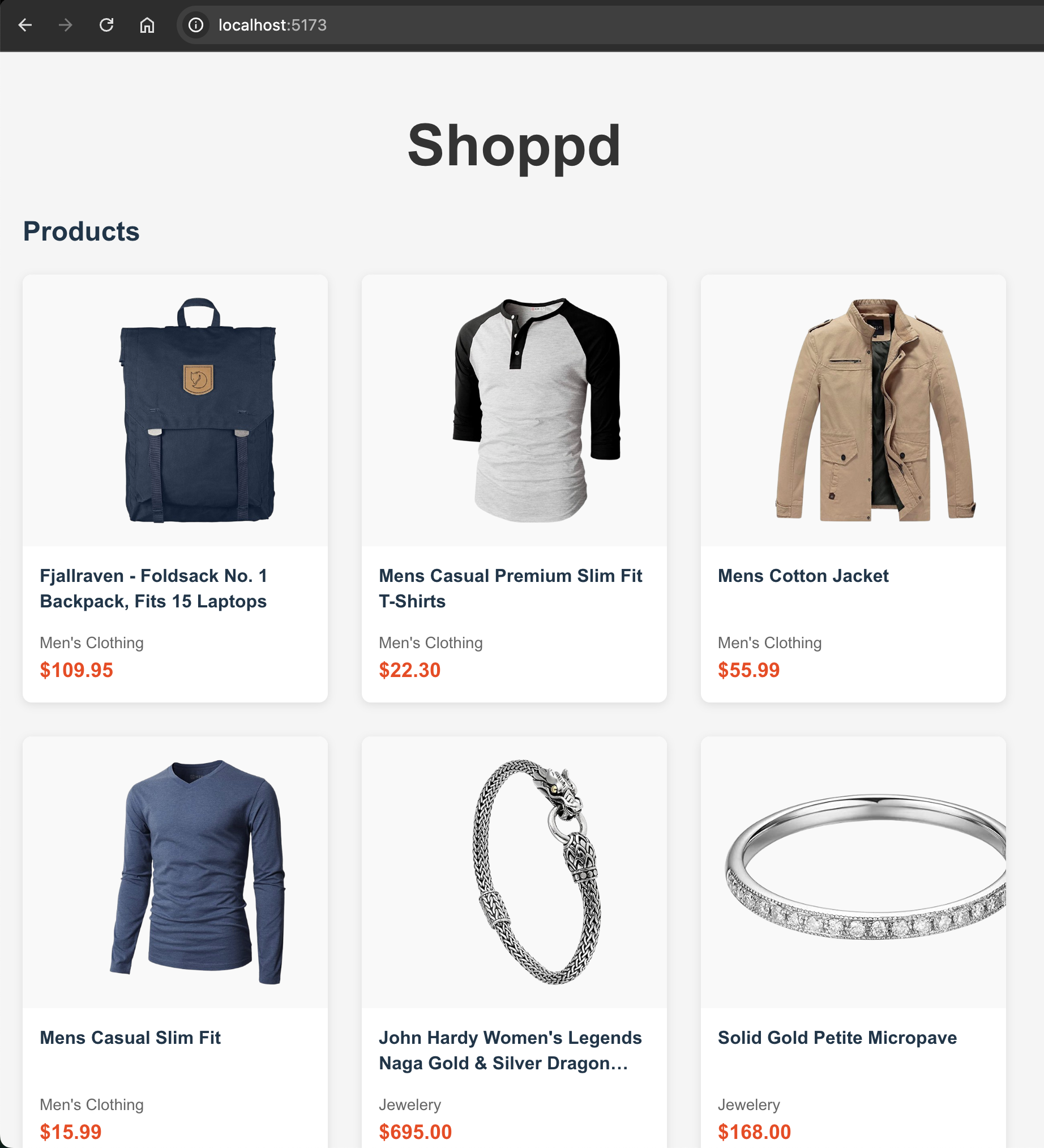

After a few minutes, Claude produced this. Holy smokes! It's a functioning website! And it even added CSS!

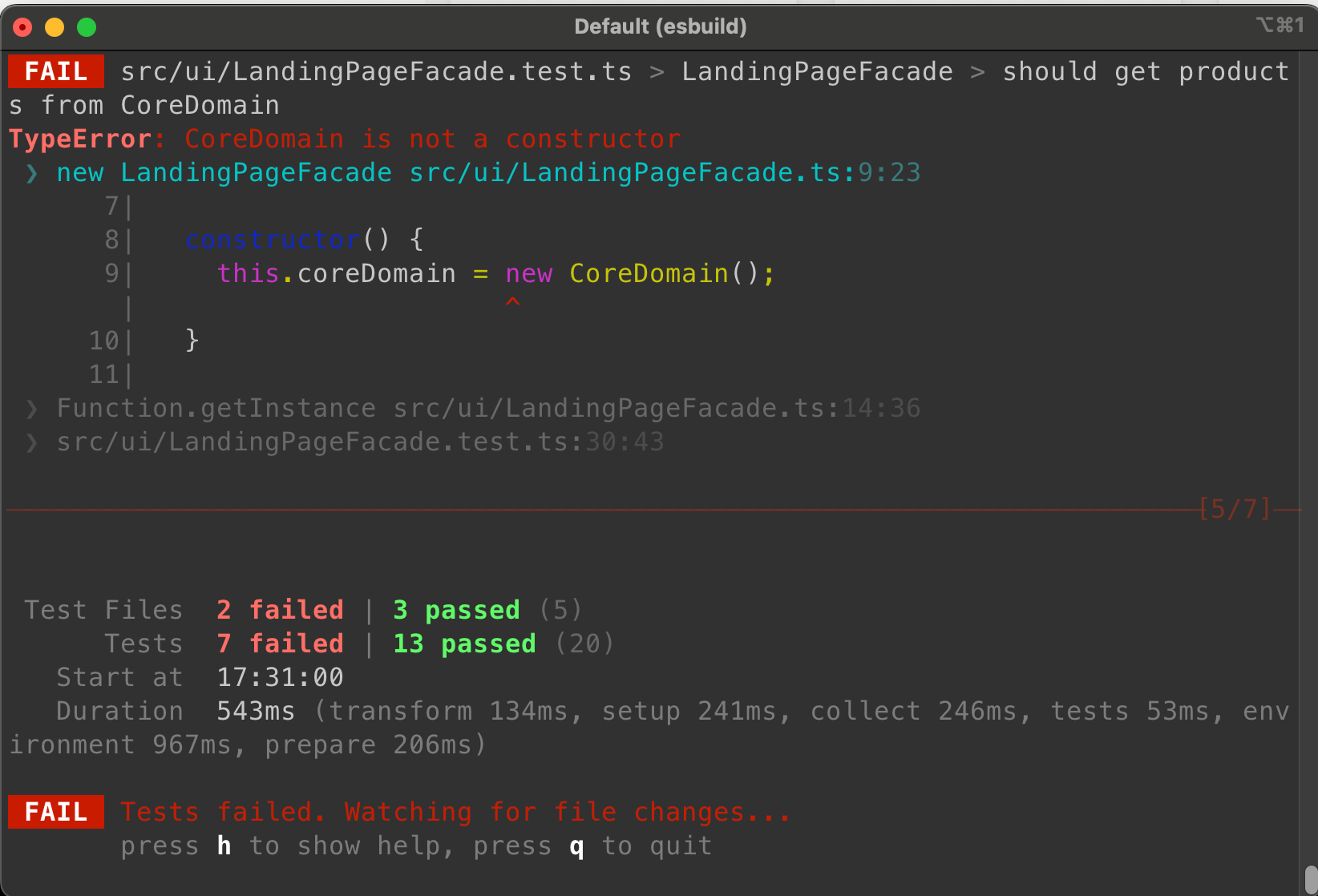

The unit tests, however, didn't work out of the box. Still, I'm impressed.

I went through the code and made changes to fit my initial prompt's requirements fully. Here's the result, which still has some failing tests that I'm not going to take time to fix, but you'll get the point.

Part 1: The Landing Page

The UI Port

The LandingPageComponent is a display only component. There is no fancy business logic. All non-display logic is offloaded to the other parts of the DDD architecture.

import { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

import { LandingPageFacade } from './LandingPageFacade';

import { Product } from '../domain/types';

const LandingPageComponent = () => {

const [products, setProducts] = useState<Product[]>([]);

const [loading, setLoading] = useState<boolean>(true);

const [error, setError] = useState<string | null>(null);

const landingPageFacade = new LandingPageFacade();

useEffect(() => {

const fetchProducts = async () => {

try {

setLoading(true);

await landingPageFacade.getProducts();

setProducts(landingPageFacade.products);

setError(null);

} catch (err) {

setError('Failed to fetch products');

} finally {

setLoading(false);

}

};

fetchProducts();

}, []);

if (loading) {

return <div>Loading products...</div>;

}

if (error) {

return <div>Error: {error}</div>;

}

return (

<div className="landing-page">

<h2>Products</h2>

<div className="products-grid">

{products.map((product) => (

<div key={product.id} className="product-card">

<img src={product.image} alt={product.title} className="product-image" />

<h3>{product.title}</h3>

<p className="product-category">{product.category}</p>

<p className="product-price">${product.price.toFixed(2)}</p>

</div>

))}

</div>

</div>

);

};

export default LandingPageComponent; You may notice on line 10 that we "new up" the LandingPageFacade. This is how we leverage our Singleton Factory Pattern to stitch together the necessary parts of our DDD architecture. The downside to this, compared to a Dependency Injection (DI) Framework, is that we have to mock the entire import from './LandingPageFacade' in our tests, but this is a small price to pay to avoid the massive overhead that a DI Framework (like Angular Modules) would require us to manage. We just want to separate out the parts of our logic into the right "buckets" for now, so we forego DI.

Now that we've seen all that there is to see in the LandingPageComponent, let's move on to the LandingPageFacade , which connects our UI port to the CoreDomain.

Part 2: The LandingPageFacade

An intermediate, evergreen, UI service layer

import { CoreDomain } from '../domain/CoreDomain';

import { Product } from '../domain/types';

export class LandingPageFacade {

private static instance: LandingPageFacade;

private coreDomain!: CoreDomain;

constructor() {

if (!LandingPageFacade.instance) {

this.coreDomain = new CoreDomain();

LandingPageFacade.instance = this;

}

return LandingPageFacade.instance;

}

public async getProducts() {

await this.coreDomain.getProducts();

}

public get products(): Product[] {

return this.coreDomain.products;

}

}

The LandingPageFacade "news up" a reference to the CoreDomain in its constructor, then invokes this.coreDomain.getProducts() as a pass-through method. It is nothing more than a connector between the UI port and the CoreDomain , but it is important because if we ever swap out the UI port in React for something like VueJS or Angular the only code that we must change is in LandingPageComponent. Everything else should "just work" once we connect the updated component to the LandingPageFacade appropriately.

Part 3: The Core Domain

This is the evergreen core where your business lives

We now arrive at the CoreDomain which is the cornerstone of the whole architecture.

import { StateFacade } from '../state/StateFacade';

import { InfraFacade } from '../infra/InfraFacade';

import { Product } from './types';

export class CoreDomain {

private static instance: CoreDomain;

private stateFacade!: StateFacade;

private infraFacade!: InfraFacade;

constructor() {

if (!CoreDomain.instance) {

this.stateFacade = new StateFacade();

this.infraFacade = new InfraFacade();

CoreDomain.instance = this;

}

return CoreDomain.instance;

}

public async getProducts(): Promise<void> {

try {

const products = await this.infraFacade.getProducts();

this.setProducts(products);

} catch (error) {

this.setProducts([]);

this.setErrors([error instanceof Error ? error.message : 'Failed to fetch products']);

}

}

private setProducts(products: Product[]): void {

this.stateFacade.setProducts(products);

}

private setErrors(errors: string[]): void {

this.stateFacade.setErrors(errors);

}

public get products(): Product[] {

return this.stateFacade.products;

}

public get errors(): string[] {

return this.stateFacade.errors;

}

}

Business logic should live here, but this does not mean that Infrastructure logic, or State logic, etc. should live here. Business rules that you want to capture in code, that should not change for some time, should all live here and if necessary be split off into helper classes that also reside in /src/domain. The reason for this is that you can remove the State port, the Infrastructure port, and the UI port, then replace them with alternatives, but your core business code will remain untouched. If you have written good unit tests here, you have effectively future-proofed your critical business logic by writing it in evergreen JavaScript (or, in our case, TypeScript).

The CoreDomain orchestrates activity between all the other pieces of the DDD architecture. If it calls the Infrastructure port via the InfraFacade to fetch data, it then invokes this.stateFacade.setProducts() with the value of that response, but it does not retain that state in the CoreDomain. It simply directs it to the State port.

Speaking of fetching, let's now move to the InfraFacade.

Part 4: The InfraFacade

Your evergreen infrastructure service layer

import { Product } from '../domain/types';

export class InfraFacade {

private static instance: InfraFacade;

constructor() {

if (!InfraFacade.instance) {

InfraFacade.instance = this;

}

return InfraFacade.instance;

}

public async getProducts(): Promise<Product[]> {

const response = await fetch('https://fakestoreapi.com/products');

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error(`HTTP error! status: ${response.status}`);

}

return response.json();

}

}

Here is our entire Infrastructure port, contained within this Facade. In a more complex application, such as one that requires us to pass auth tokens to an API or has various headers that we need to set, we would abstract this out further so that the InfrastructureFacade would call the ApiService and the ApiService could handle setting all of our necessary headers. Since we don't need it here though, we just use the InfrastructureFacade

Part 5: The Fetch API

The API port

Currently, this is our entire API port.

const response = await fetch('https://fakestoreapi.com/products');For a production application, we would almost certainly abstract this out into its own ApiService so that we could incorporate things such as axios, GraphQL, etc. into our Infrastructure Port as we wish.

Part 6: The StateFacade

Your evergreen state service layer

import ShoppdStore, { setProducts, setErrors } from './ShoppdStore';

import { Product } from '../domain/types';

export class StateFacade {

private static instance: StateFacade;

constructor() {

if (!StateFacade.instance) {

StateFacade.instance = this;

}

return StateFacade.instance;

}

public setProducts(products: Product[]): void {

ShoppdStore.dispatch(setProducts(products));

}

public setErrors(errors: string[]): void {

ShoppdStore.dispatch(setErrors(errors));

}

public get products(): Product[] {

return ShoppdStore.getState().products;

}

public get errors(): string[] {

return ShoppdStore.getState().errors;

}

}

The StateFacade is simply a pass-through service that allows us to update the state of our application, regardless of the state library we choose to utilize under-the-hood.

If we wanted to swap out Redux for our own homegrown RxJS Observable store at some point, we could simply update this facade and the Store itself, and no other code in our application would have to change. Rewriting two files instead of one hundred is a great tradeoff for applications that will be around for a long time.

Part 7: Redux

The Redux Store

import { configureStore, createSlice, PayloadAction } from '@reduxjs/toolkit';

import { Product, AppState } from '../domain/types';

const initialState: AppState = {

products: [],

errors: []

};

const shoppdSlice = createSlice({

name: 'shoppd',

initialState,

reducers: {

setProducts: (state, action: PayloadAction<Product[]>) => {

state.products = action.payload;

},

setErrors: (state, action: PayloadAction<string[]>) => {

state.errors = action.payload;

}

}

});

export const { setProducts, setErrors } = shoppdSlice.actions;

const ShoppdStore = configureStore({

reducer: shoppdSlice.reducer

});

export type RootState = ReturnType<typeof ShoppdStore.getState>;

export type AppDispatch = typeof ShoppdStore.dispatch;

export default ShoppdStore; Finally, we arrive at our Redux Store, ShoppdStore . This provides us all of the power of Redux in a self-contained "bucket" in our codebase. Decisions will have to be made regarding tradeoffs of whether to include some business logic in our State port when certain Actions are dispatched, or we can simply use it as a value store and choose to add additional complexity in our CoreDomain and make additional calls back to the Store to update interdependent values when things change. Whether we offload that to the CoreDomain or whether we choose to do it here in the ShoppdStore depends on how we think the business will evolve in the long-term.

Conclusion

Is DDD overkill for the UI? Probably for most businesses. However, if you are operating at the enterprise level and beyond, it could be a helpful tool that will enable you to avoid painful app-wide changes that add risk to your business over the long-term.

I'll also note that I'm very impressed with Claude's performance here. AI shortened the time it took me to code the example for this post from days to about two hours. That's a significant gain, and for greenfield projects its an indication that maybe DDD isn't such a bad thing after all. It will increase your boilerplate code, for sure, but that boilerplate will allow you to make small changes to your codebase later rather than sweeping changes that risk bringing a project down.

DDD forces short-term pain for long-term stability, and for businesses that must iterate and release quickly, it's probably not for you. Most businesses die because they move too slowly, not because they move too quickly, so only your team can decide if the long-term gains of DDD are right for you.

But in any case: now you've seen how to do it! So give it a try. If you hate it, it will just get rewritten in five years anyway, right?